The Exits are Located Here, Here and Here: The North East’s Links to Crash Bar Exits

In this blog, Cathryn takes a look at the North East’s links to the invention of the crash bar exit, and the tragic event that inspired its invention.

We’ve all seen crash bar exits, but most of us have probably paid no thought to them. The crash bar was designed by Robert Alexander Briggs, who was granted a patent in 1892. His creation was motivated by events in Sunderland nine years earlier, which we will now take a look at.

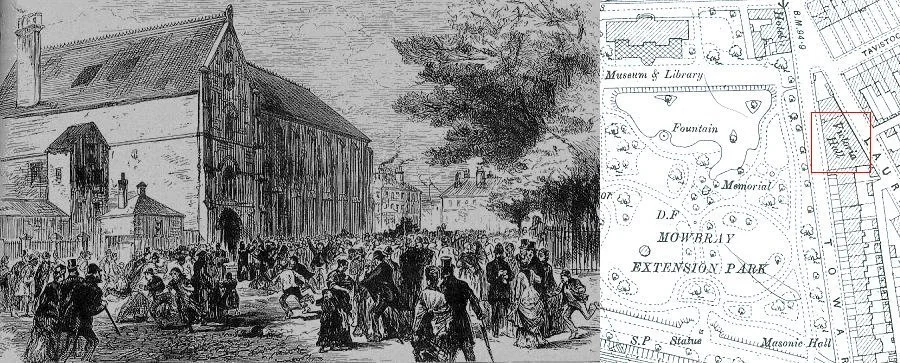

Standing next to Mowbray Park in the centre of Sunderland, Victoria Hall was built in 1872 with funding from Edward Backhouse a prominent philanthropist and Quaker minister. Designed in the then fashionable neo-gothic style it served as a place for entertainment and public meetings. On the 16th of June 1883 around 2000 children took their seats for a magic show given by travelling entertainers Alexander and Annie Fay. In the run up to the performance Alexander Fay and his assistants went around all the schools in Sunderland selling tickets and distributing flyers. The price of a ticket was one penny, the prices deliberately kept low so that, “even the humblest could attend.” As well as the cheap ticket price, the Fays had something else to attract ticket sales. Prizes! Adverts for the show stated that, “Every child entering the room will stand the chance of receiving a handsome present, books, toys, etc.” The Fays’ marketing campaign was a success, and the theatre was nearly full, (Victoria Hall could seat somewhere between 2500 and 3000 people).

The Fays had performed their magic show to, “thousands of delighted children throughout England.” So, they had no reason to believe that the Sunderland performance would be any different. In fact, until the end of the show everything went smoothly. The only hiccup was the smoke from one of the tricks had made a few of the children in the front rows sick. The giving out of the promised prizes then began. This is where it all went wrong. It was announced that children with certain numbered tickets would be given prizes as they left the theatre. At the same time Alexander Fay and his assistants started to throw toys and sweets into the audience. These only reached the ground level with none going to the upper levels. This of course caused upset with those sat in the gallery. Several years later, survivor William Codling Jr described this,

“We in the gallery howled with rage. […] The conjuror informed us that a man was already on his way up the stairs with a basket of toys for us. So, we obligingly rose en masse and went down the stairs to meet him.”

There were around 1100 children sat in the gallery, and very few adults to supervise them. Whilst the children’s tickets had cost a penny each, adult tickets were 3d each. This meant that they were unaffordable to the mostly working-class audience. This lack of adult supervision paired with the excitement of the children would prove disastrous.

As the children descended the stairs they came to a door partway down. This door had been bolted at some point so that only one person at a time could go through. This had been in order to allow for orderly ticket checks, but now it blocked the children’s passage down the stairs. The narrow exit (of around 20 inches) and the number of children coming down the stairs at the same time led to a massive crush. By the time the few adults present realised what was going on the crush was about 20 deep. A few children were pulled through the gap in the door, but this was slow going. Caretaker, Frederick Graham led around 600 children to safety via another staircase. Eventually the door was pulled off its hinges. After 30 minutes all the children caught in the crush were bought out. The crush killed 183 children between the ages of 3 and 14, with another 100 being seriously injured. Some families lost all their children in the event, and an entire Sunday school class was killed.

Following the incident a fund was set up to help pay for the children’s funeral costs. A total of £5769 was raised with £50 being donated by Queen Victoria. (Victoria’s donation is mentioned in William McGonagall’s poem about the event, The Sunderland Calamity). These not only paid for the funerals, which were held over the course of a week, it also paid for a memorial. The memorial, a marble statue of a mother holding her dead child was placed in Mowbray Park, close to the site of the disaster. It was later moved to Bishopwearmouth cemetery before being returned to Mowbray Park in 2000. Two inquiries were held in the aftermath, although neither was able to determine who had bolted the door. The disaster led to the passing of legislation which required places of public entertainment to have minimum numbers of exits which opened outward, (the door in Victoria Hall was inward opening). The Fays themselves were criticised but faced no legal consequences. They continued to perform but never again for children, nor did they return to Sunderland. Victoria Hall itself continued to be used until it was destroyed by a German bombing raid in 1941. Having become associated with the disaster of 1883, it wasn’t widely missed.